It’s considered one of the more taboo subjects given the ’embarrassing’ nature of the topic, but a large amount of HNPP sufferers appear to experience problems with their gut. And not in the instinctual kind of way. Digestive issues could be more closely linked to the condition than you may think.

While research surrounding this particular issue is limited, linking HNPP to other areas of the body could provide more information surrounding this topic. Quoting those who have spoken to noted medical practitioners researching HNPP, sufferers with the inherited disorder are more susceptible to problems with digestion “due to Schwann cells not forming properly in the embryonic stage”.

“I would take the position that unless a problem clearly has a neurological basis then it should not be attributed to HNPP.”

– Gareth J. Parry, M.D

Disclaimer: Please ask your medical practitioner for more information. This article is based on various research, journals and testimonies.

Prior to this new information, Gareth Parry MD, the Professor and Head, Department of Neurology, University of Minnesota said that symptoms such as digestion issues should not be attributed to HNPP.

Dr Parry stated: “I would take the position that unless a problem clearly has a neurological basis then it should not be attributed to HNPP. The only symptoms that I would attribute to HNPP largely without question would be numbness, paresthesias (pins and needles, tingling, etc) and weakness.”

Why is this important?

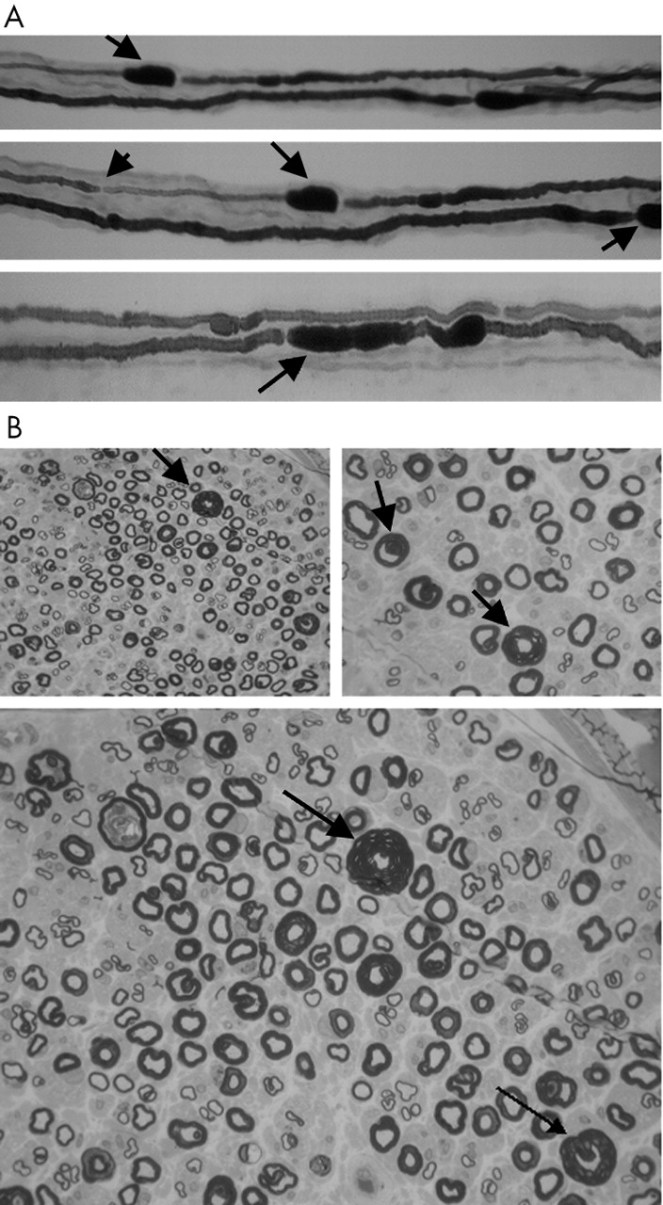

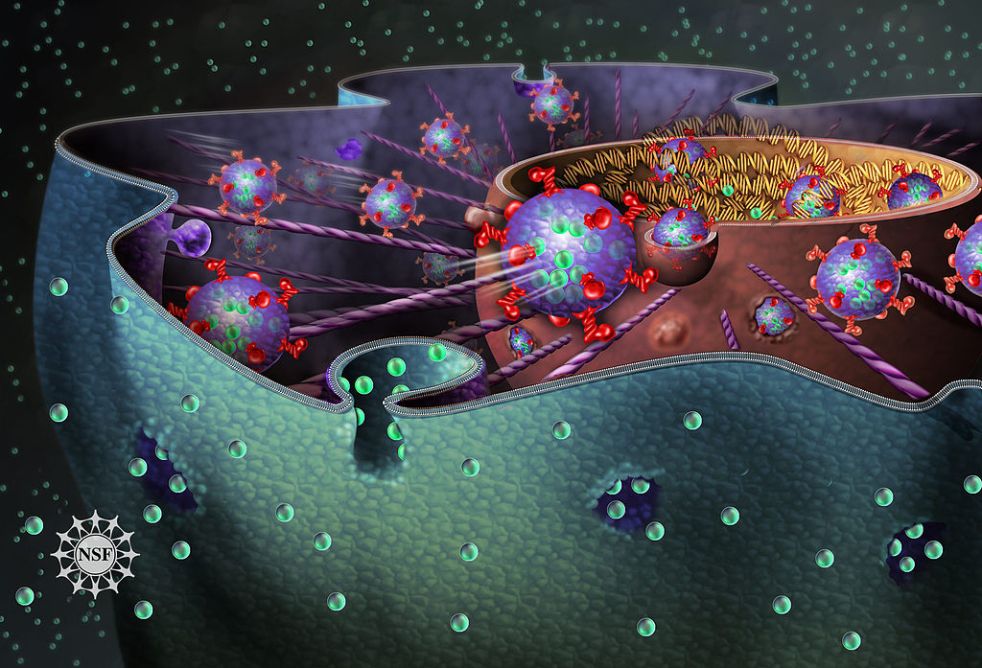

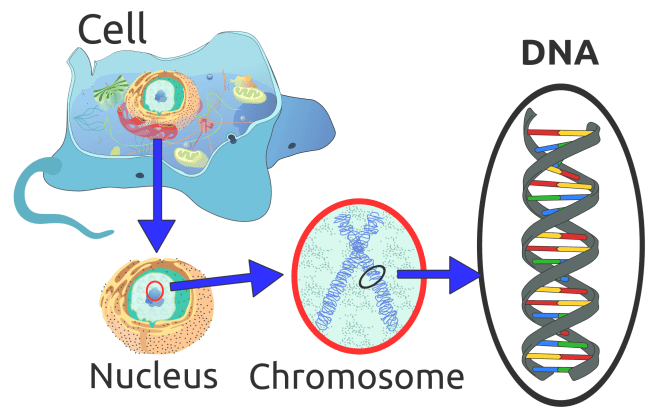

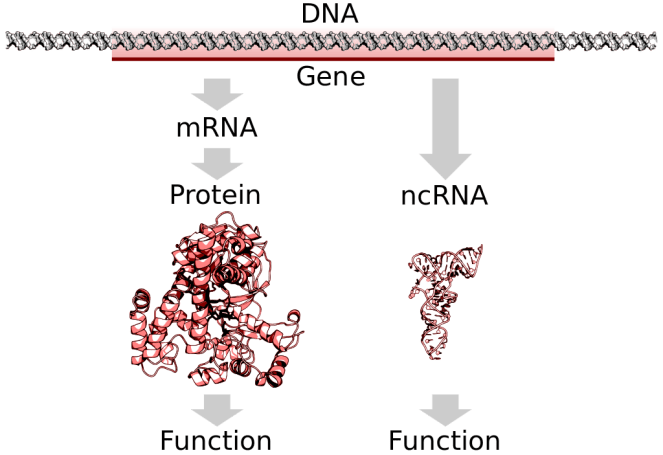

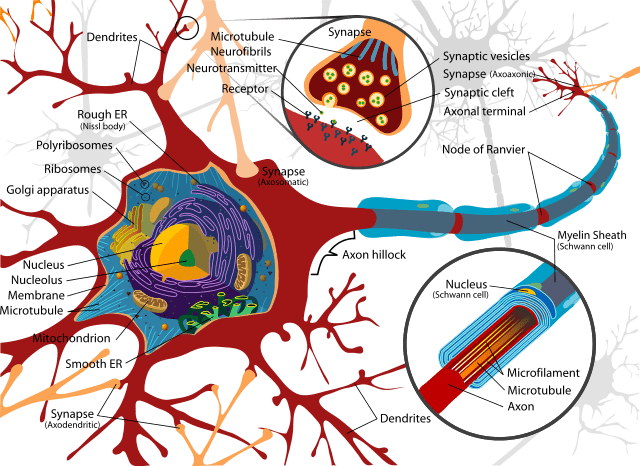

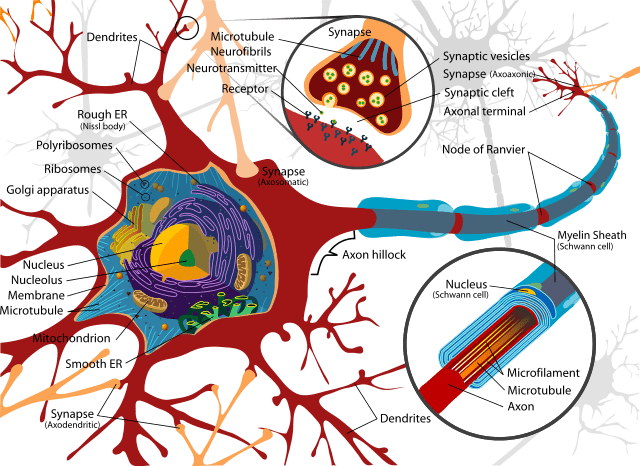

Schwann cells are vital in functioning to support neurons in the peripheral nervous system. A nerve cell communicates information to distant targets by sending electrical signals down a long, thin part of the cell called the axon. In order to increase the speed at which these electrical signals travel, the axon is insulated by myelin, which is produced by the Schwann cell. It is affected in a number of demyelinating disorders including the sister condition of HNPP called Charcot Marie-Tooth disorder.

Myelin twists around the axon like a jelly-roll cake and prevents the loss of electrical signals. Without an intact axon and myelin sheath, peripheral nerve cells are unable to activate target muscles or relay sensory information from the limbs back to the brain.

Changeable environment within nerve injury especially the scarring time can limit Schwann cells proliferation, according to a 2011 study. Unlike in CMT, the number of total Schwann cells is seen to increase, as stated by authors of the 1998 report Fate of Schwann cells in CMT1A and HNPP.

This is reiterated in the 1998 research Neuronal Degeneration and Regeneration, where the authors state: “The reduced expression [of PMP22] would result in an extended proliferation [of Schwann cells] and in excess of myelination and thus the formation of hypermyelinated tomacula as observed in HNPP. The observation of two Schwann cells forming one myelin sheath in HNPP is in line with this theory.”

Similar to autonomic neuropathies, such as diabetic neuropathy, abnormalities reported include proliferation of Schwann cells, atrophy of denervated bands of Schwann cells, axonal degeneration in nerve fibres, primary demyelination resulting from secondary segmental demyelination related to impairment of the axonal control of myelination, remyelination, as well as onion-bulb formations.

At present, the link between how the proliferation of Schwann cells itself can cause issues with digestion and HNPP has not been established, so it may be some time before the research is more widely available.

Autonomic neuropathy and HNPP

It’s vital to understand the connection between HNPP and autonomic neuropathy because AN has been proven to include symptoms such as gastrointestinal issues. As the name implies, the autonomic nervous system is responsible for monitoring the functioning of the organs that act largely unconsciously and regulates bodily functions such as the heart rate, digestion, and respiratory rate. While there are many elements where hereditary neuropathy and AN diverge, there are certain areas where they converge but haven’t been studied.

In the 2015 report Two Siblings with Genetically Proven HNPP and Autonomic Neuropathy, a brother and sister who both had the deletion of PMP22, also had symptomatic autonomic dysfunction confirmed by autonomic testing.

The researchers say: “Autonomic testing, performed due to autonomic symptoms including positional dizziness, confirmed the presence of autonomic dysfunction. The brother had neurocardiogenic syncope and adrenergic dysfunction but a normal QSART. The sister showed distal reduction of QSART response, mild symptomatic orthostatic intolerance with mild adrenergic dysfunction and intact cardiovagal and sudomotor function.”

It may be coincidental that the siblings had autonomic dysfunction on top of HNPP, however the authors conclude: “HNPP can uncommonly be associated with an autonomic neuropathy. It is important for clinicians to be aware of the potential presence of autonomic symptoms, which may contribute to poor quality of life for these patients.”

In a 2015 investigation into the link, a patient with HNPP was found to also have severe orthostatic hypotension – low blood pressure – which is generally associated with autonomic neuropathic symptoms which affects the central nervous system.

The authors say: “through exome-sequencing analysis, we identified two novel mutations in the dopamine beta hydroxylase gene. Moreover, with interactome analysis, we excluded a further influence on the origin of the disease by variants in other genes. This case increases the number of unique patients presenting with dopamine-β-hydroxylase deficiency and of cases with genetically proven double trouble.”

Dopamine-β-hydroxylase deficiency is rare form of autonomic dysfunction which affects the central nervous system attacking the functioning of the heart, bladder, intestines, sweat glands, pupils, and blood vessels. Not all are neuropathy related.

Again, these cases could be purely serendipitous given how rare they are portrayed to be, but it is apparent that more research in this area is required.

Other types of autonomic neuropathy

In the case of autonomic diabetic neuropathy, George King, MD, Director of Research and Head of the Section on Vascular Cell Biology at Joslin Diabetes Center says: “Nerves are surrounded by a covering of cells, just like an electric wire is surrounded by insulation. The cells surrounding a nerve are called Schwann cells. One theory suggests that excess sugar circulating throughout the body interacts with an enzyme in the Schwann cells, called aldose reductase. Aldose reductase transforms the sugar into sorbitol, which in turn draws water into the Schwann cells, causing them to swell.

“This in turn pinches the nerves themselves, causing damage and in many cases pain. Unless the process is stopped and reversed, both the Schwann cells and the nerves they surround die.” Sorbitol, which can be taken as an enzyme, is said to have laxative effects and does not get broken down in the small intestine, and causes water to be retained. When glucose is converted to sorbitol via the enzyme aldose reductase it results in a decrease in tissue myoinositol, with far-reaching effects throughout the nervous system.

According to the 2000 study The Diabetic Stomach: Management Strategies for Clinicians and Patients, author Gerald Berstein, M.D., says: “In the gastrointestinal tract, [diabetic neuropathy] causes, in effect, an autovagotomy […] hyperglycemia results in cellular anatomic disruption throughout the gastrointestinal tract, but especially in the stomach. Nerve cells may swell with the loss of myelinated fibers […] In the stomach, motility may be reduced in the antrum and proximal stomach. There may also be pylorospasm.”

Gastroparesis, or delayed gastric emptying, is a rare feature of diabetic autonomic neuropathy. This long-term condition means food passes through the stomach more slowly than usual. It’s not always clear what leads to gastroparesis. But in many cases, gastroparesis is believed to be caused by damage to the vagus nerve that controls the stomach muscles.

“A doctor explained it as if it was similar to diabetes. Where our bodies should be able to digest at any given moment but in ours the signals just don’t always get there. Resulting in a case of this food ready and there but unable to be digested for my self it always results in diarrhoea and horrible stomach pains. But as with everything with this disease it varies greatly from person to person.”

Charcot Marie-Tooth disorder forum on Reddit

As with the above, there is virtually no information in regards to gastroparesis linked to HNPP, however, episodes of gastroparesis has been recorded in those with Charcot Marie-Tooth disorder.

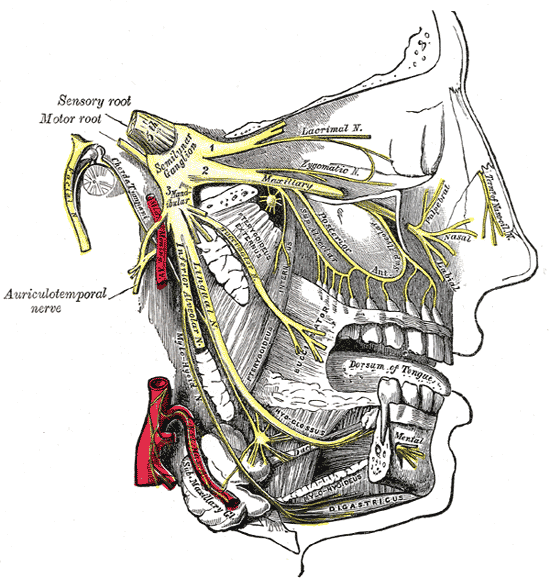

The vagus nerve and HNPP

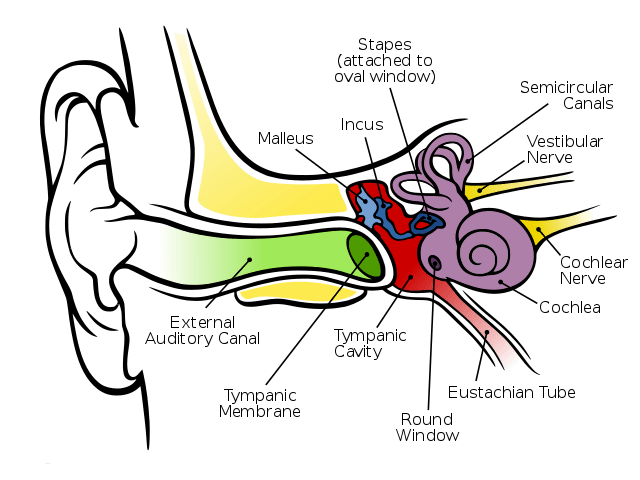

The vagus nerve helps manage the complex processes in your digestive tract, including signalling the muscles in your stomach to contract and push food into the small intestine. A damaged vagus nerve can’t send signals normally to your stomach muscles. This may cause food to remain in your stomach longer, rather than move normally into your small intestine to be digested.

In one study, esophageal dysphagia in HNPP – the sensation of food sticking or getting hung up in the base of your throat or in your chest after you’ve started to swallow – was compared to bovine tomaculous neuropathy. In this particular condition, cows were seen to have “bilateral vagus nerve degeneration, with nerve lesions similar to those seen in tomaculous neuropathy in humans.”

The research surrounding HNPP by Brazilian scientists at the Neurology Division, Internal Medicine Department, Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR), however, concludes that this was seen to be “rare” and that HNPP “should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with atypical swallowing dysfunction.”

The bovine study should also be taken with a pinch of salt given the difference of the physiognomy between animals and humans. Authors of A Study of the Pathology of a Bovine Primary Peripheral Myelinopathy, state similar traits such as the thickening of myelin sheaths within HNPP was observed in the cows in question. At the same time, 1995 research reports: “Clinical signs of dysphagia and chronic rumenal bloat developed after weaning which were attributable to bilateral vagus nerve degeneration.”

They go on to add: “The lesions are similar to those seen in the tomaculous neuropathies

of man.”

It may be the first signs of the scientific community attempting to make the leap between hereditary peripheral neuropathy with the vagus nerve as well as autonomic-type dysfunctions attacking the digestive system. However, without the words on paper and significant credibility, it’s hard to make a judgement.

Read: When HNPP ’causes breathing problems’